Introduction

The Bidayuh people of Sarawak, Malaysia live in towns and villages around the capital city of Kuching (Wikipedia 1). An alternate name for Bidayuhs, meaning 'inhabitants of land', is Land Dayaks, a name given during the reign of James Brooke. The Bidayuh are the second largest Dayak ethnic group behind the Iban. Bau district is one of five near Kuching where most Bidayuh villages are found. The authors of this report, Haslina Jais and Blair Daly, were fortunate to meet and interview Peter Tiwet anak Tuen, a Bidayuh and a longtime resident of Kampung Tanjong in Bau, Sarawak.

The town of Bau is 30km southwest of Kuching and is known for its historic gold mines which were discovered by Chinese miners in the 1840s (Wikipedia 2). The mines were closed in 1921 by which time all the easily extractable gold had been removed, but when hard times hit during the Great Depression Chinese miners headed back in for whatever profit could be made. Since then, several different companies have controlled the mines and made them operable off and on through the present day.

On Saturday February 14th and Sunday March 8th the authors of this report drove approximately one hour from the UNIMAS campus northwest to Kuching and then southwest to Bau. Kampung Tanjong is where our interviewee Peter grew up and has lived for the past thirty years. As far as we know this village has no major historical importance. It was among several Bau villages that made the news this year in early January because its residents were being told to prepare for evacuation due to flooding. The number of people living here has declined from over 300 thirty years ago to less than 200 today due to fewer and fewer young people choosing to make their homes and raise their families in the village.

I. Birth, Japanese Occupation

Peter's birth took place in circumstances quite dissimilar to those of the authors. He was born in 1944 inside a home in the foothills of Mt. Singai. His mother did not benefit from the modern technology or medicinal comforts that hospitals provide but rather was aided by other women who had already gone through the process. Tiwet was the name given to Peter by his father, Tuen, and all of his children retain this name as their last name (e.g. Gloria anak Tiwet); however, Peter has preferred the Christian name he was given by his priest upon being baptized at a young age in the Catholic Church.

In Sarawak, the war breaking out in Europe in 1939 seemed a long way off and not likely to affect the country any more than World War One had (Rawlins 1965, 139). Britain, who had promised protection to Sarawak, sent a small group of Punjabi soldiers here, but no one thought this Borneo state would soon be engulfed in the war (Rawlins). In fact, many were busy preparing for Sarawak's centennial celebrations just a few years before Peter was born. (Englishman James Brooke was handed control of Sarawak by the soon-to-be Sultan of Brunei, Rajah Muda Hassim, in 1841. By 1941 Sarawak was still ruled by the Brooke family, specifically James' second nephew's son Charles Vyner.) The centennial celebrations took place in September; by the year's end Sarawak was under Japanese occupation. Not only Sarawak but also Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, the Philippines, and Indonesia fell to the unexpected Japanese offensive in a matter of weeks in late 1941. Kuching was captured on Christmas Day.

The Japanese takeover of Sarawak during World War Two did not much affect Peter personally – as it came to an end when he was one year old – but it did negatively impact his family. He views that brief period as a time of severe hardship for the people of Sarawak, including the Bidayuhs of Kampung Tanjong. Japanese soldiers were a constant threat to their livelihood and well being, creating an environment of fear. Tending to be highly suspicious of the locals, soldiers punished villagers brutally if they perceived the slightest threat or sign of disrespect, being known to beat people for failing to bow to them in deference. Peter's father experienced their wrath firsthand. He asked a man sitting next to him in a restaurant whether the rumor was true that the Japanese would soon be leaving. This stranger turned out to be working for the Japanese. Peter's father's question was reported, and he was beaten and left for public humiliation outside the courthouse in Kuching. Rapes of village women and girls were not uncommon. To make girls less attractive, parents would intentionally avoid washing their daughters and would smear their hair and faces with dirt. Peter's parents routinely hid his older siblings in a secret compartment inside their chicken coop whenever the soldiers came around.

Common goods like food and clothing were much harder to come by as a result of the Japanese occupation. The overall disturbance to the economy caused by the military occupation made markets scarce and food less affordable. Some shops in Bau and Kuching were robbed and then destroyed. The inaffordability of food combined with Japanese soldiers feeling free to confiscate any village's crops forced the people of Kampung Tanjong to rely more on bartering and on collecting food such as fruit and roots from the jungle. Peter's family had to eat a diminished quantity and variety of foods, so their diets lacked nutrition. Days of eating nothing but rice mixed with tap water and salt were not unknown.

Not only commerce but also communication, transportation, and education were interrupted from 1941-1945. Normal modes of contacting the world outside the village were cutoff by the Japanese who were wary about allowing too much unmonitored interaction. New roads were built only if they facilitated Japanese consolidation of the land. Peter's father often had no choice but to remain in the village. Schooling was not a priority of the Japanese administration, so Peter's older siblings were for the most part denied this right during the occupation.

Peter was one year old in September 1945 when the Australian army entered Kuching and the Japanese formally surrendered.

II. Schooling, Sarawak Becomes a Colony, Communists

Despite being a bright student who was twice promoted to skip a year, Peter was educated only through primary school. He attended St. Peter's missionary school, a short walk from his home, where his teacher was a local but the medium of instruction was English. Many Bidayuhs in Peter's generation attended English medium missionary schools. This explains why their grasp of the English language is usually equal to or better than their grandchildren's, many of whom have gone to Malay medium government schools. Peter moved to a different village to complete Primary Six, but he did not advance beyond that into secondary school or university. His mother died when he was a child and his father remarried and was not concerned about his education. Without a mother and father to guide him at a young age, he says it is only by the grace of God that he has generally made good decisions and turned out alright. He spent a few idle years "just being a boy" back in Kampung Tanjung before taking a job at age seventeen. He collected specimens and blood samples of jungle animals and handed them over to be sent to a research institute at the School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in England. This was from 1960 to 1963, during which time Sarawak was a British colony.

When Rajah Vyner Brooke returned to Sarawak in 1946 after the defeat of the Japanese he had already decided to cede Sarawak to Britain (Rawlins, 142). The place was in bad condition with hungry people, disorganized trade, neglected plantations, and inactive oilfields. Peter's family felt the effects of Sarawak lagging behind the world in development, with revenue being insufficient to support services like education, health, and roads. These tasks, thought Vyner Brooke, could be better managed by a colonial power like Britain. Additionally, the Rajah was getting old and had no sons and no heir to which he thought fondly of handing over Sarawak. For these reasons he recommended cession. The bill passed the State Council by a narrow margin and Sarawak became a British colony in July of 1946 (Rawlins, 145).

It was not long before the growing communist activity in Sarawak became the number one enemy of the British administration. The most intense conflict took place in the 1950s when random communist bombings would kill a small number of people here and there and British troops retaliated by stepping up the intensity of their manhunts. Severe Emergency Regulations were enacted in Malaya starting in 1948 and lasting twelve years (INSAN 1979, 139). As during the Japanese occupation, this was a scary time to be a villager around Kuching. Security was very tight and once again freedom of communication and movement were interrupted. Peter's family had been warned about the evils of communists by the British, but Peter's father decided it was in the best interest of his family to accommodate both sides of the conflict rather than make any enemies. He helped feed, hide, and inform four communists in particular who over time became friends of the family. They hid deeper and deeper in the jungle as the British stepped up their searches, offering rewards to those who gave useful information and threatening those perceived to be aiding communists. One night the four communist friends were actually caught and killed when the British raided their camp. This all took place during Peter's childhood.

III. Bidayuhs, Eventful 1963, Work

Returning to the subject of the Bidayuh people, the 1960 census recorded Land Dayaks, or Bidayuhs, as Sarawak's fourth most populous ethnic group behind the Sea Dayaks or Iban (32%), the Chinese (31%), and the Malays (17%) (Rawlins, 189). They made up 8% of Sarawak's population, but the category of Land Dayaks encompassed several indigenous groups found in southern Sarawak that are broadly similar in language and culture (Wikipedia 1). Bidayuhs have and continue to live in what used to be Sarawak's First Division, within 40km of Kuching, and are closely related to groups across the Indonesian border in West Kalimantan (Wikipedia 1). Tradition holds that Bidayuhs live on forested hills and even mountain tops for protection from Iban pirates who used to attack them (Rawlins, 191). Hence the family joke that Peter was born on top of Mt. Singai, which towers above Kampung Tanjong.

The year 1963 was momentous for both Sarawak and Peter. Sarawak achieved full independence as a member state of the Federation of Malaysia. Peter believes this change could neither be said to be generally good nor bad for his family and fellow villagers; rather, it presented a range of pros and cons. One positive result was that the "Borneoisation" of the state administrative government, which was called for especially by the federal government of Malaysia, meant that many new government posts opened up as they were vacated by British. On the negative side, Sarawak joining Malaysia meant that some of its people were subject to forms of discrimination and unequal treatment based on race that they had not experienced prior. Peter is critical of Kuala Lumpur's focus on the development of cities at the expense of sufficient attention to rural areas.

Also in 1963, nineteen year old Peter got married and landed a new job working as a caterer in the mess hall of the 99 Gurkha Brigade stationed at Green Road in Kuching. This British contingent was present mainly to defend Sarawak from Indonesia which was expressing hostile displeasure over Sarawak's joining of Malaysia. Peter's wife also gave birth to their first child in 1963. These three major events in Peter's life at age nineteen remind us of the social transformation that has taken place. Today it is very uncommon for young Sarawakians to wed, take a full time job, and have their first child all before turning twenty years old.

Peter liked his job working for the British army for three years because they treated him nicely, praised his English speaking, and tipped well. At the time he was renting an eighteen ringgit per month room in Kuching for his family of three. He was sorry that in 1966 the brigade was apparently no longer needed and was relocated to another country. They asked Peter to come along, but, being a family man and unfamiliar with the world outside Kuching, he declined. He proudly reports that they threw him a going away party during which he was honored with a plaque bearing his name and a word of gratitude for his fine work.

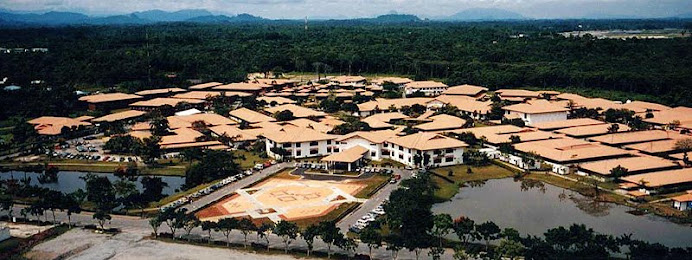

Peter immediately found a new job as a bar steward at the high-class Sarawak Club. Over a period of fifteen years he worked his way up to Acting Assistant Manager, a position which encompassed the jobs of storekeeper, public relations officer, chief steward, and purchasing officer. This was a man with no high school education but a good head on his shoulders and an honest work ethic. Having served there for so long, Peter was entitled to be promoted to the position one step higher of Assistant Manager which carried more prestige and paid better. He felt cheated when the nephew of a Sarawak government minister was appointed to the job instead. This man was university educated but had little experience, and when he came to Peter to ask for advice on how to do his new job, a betrayed Peter told him to "Go to hell!" Peter suffered a severe stroke and nearly died in 1977, but fortunately the Club helped pay for the emergency care Peter received in Kuala Lumpur. In 1988 Peter's stepfather passed away and he felt it was proper for him to return to the village to manage the paddy, the fruit trees, and the family, as his stepfather had done. Peter quit his job at the Sarawak Club, but before long he regretted this decision because he quickly ran out of money and realized how high-paying his job had been. He went back to work in 1992 as a driver for an economic development corporation known as P.P.E.S. that was closely affiliated with the Sarawak government. The job provided him some flexibility and acceptable pay as he drove the company executive around Kuching. Peter held this job until his retirement in 2005 at age sixty.

IV. Opinions

In addition to sharing his work experiences and his perspective on significant periods in Sarawak's history, Peter also volunteered opinions on a few topics about which he obviously feels very strongly.

Peter is defensive of the British and of missionary schools. He thinks that maligning the reputation of the colonial power and saying that they are the source of Sarawak's relative backwardness are easy to do today but are ultimately unfair. Governments should be judged according to their historical context, he says, and the colonial government did what it could to develop Sarawak given the resources it had. Peter went to an English medium missionary school and most of his children and grandchildren did also. He feels uneasy about the incorporation of missionary schools into the national school system, citing a rumor he heard that Muslim prayers are now being recited alongside Christian ones at a historic missionary school in Kuching. Because medical terms are all in English and so many Malay words are borrowed from the English language anyway, Peter thinks the Malaysian government's switch to using Malay as the medium of instruction in schools may not have been wise.

In his view Malaysia is not fully democratic. Having a list of "sensitive issues" about which free and open discussion is not allowed is inconsistent with democracy. Peter dislikes the Internal Security Act and perceives it to be a threat even to him, as he expressed genuine fear that he could be arrested for some of the things he was telling the interviewers. Overall, Malaysia's biggest political problem is that the government does not treat its citizens equally. He would like to see a strong leader emerge in Malaysia capable of unifying the people and in favor of treating all Malaysians like one family with no favoritism.

Additionally, Peter voiced that common refrain from the older generation that society has gotten more and more dangerous over time. For example, it is no longer safe for girls to walk by themselves at night in Kuching.

Closing

The authors of this report were very grateful for the opportunity to interview Peter who has lived well beyond both of our ages combined. It helped us to put a human face on significant periods in Sarawak's recent history and was a worthwhile exercise in Malaysian social history.

Interview Information, Challenges

Peter is the grandfather of a classmate and friend of the authors. This explains how we found, contacted, and obtained interviews with him. We met him on two occasions, February 14th and March 8th, at his thirty-year-old home in Kampung Tanjong, Bau for approximately two hours each. Along Highway 1, the village is the first one on the right after passing over Spora River headed west.

The process went smoothly with no major challenges. We were fortunate to find an older gentleman who is not shy about sharing stories and opinions and communicates so well in the English language, as one of the authors understands Malay and English while the other knows only English. Peter's granddaughter, who is a friend of the authors, accompanied us on both visits, making it easier to find the village and to break the ice between interviewers and interviewee. Our second meeting was cut shorter than any of us preferred because Peter needed to leave for evening church. The authors encountered one small confusion when we initially understood Peter's full name to be Peter Stewart. We corrected our mistake during our second meeting.

-